“At the root of this sacred rite we recognize unmistakably the imperishable need of the human being to live in beauty. There is no satisfying this need save in play.”

Johann Huizinga: Homo Ludens ⟩⟩

Play

No other theme integrates questions of such philosophical import and complexity about education, nature and art as organically as play. The personal urgency of these questions makes them particularly suitable for exploring in a conversational context. In talking and thinking together about play, we explore our ways of thinking about our identities and ideals as human beings. This course of study offers to enliven and guide this exploration by focusing on classical and modern examples of play-related topics, as well as offering a survey of the most prominent scholarly approaches to play, works of visual and literary art (film, painting and novels), as well as documentary accounts of the play experience.

Play as the Origin of Culture

Contrary to what the cover of the edition used here as illustration suggests, Johan Huizinga argues that not games, but archaic contest and ritual are the primary forms of play. Huizinga was the first to give a “definition” of play, while also insisting that play as such as indefinable, raising innumerable questions about play that have shaped philosophical inquiry ever since. What does he mean for instance when he writes that “play is freedom”? What idea of freedom is “at play” here? What are the different moral theories for which play might be relevant (utilitarian, deontological, and virtue-based)? Is play fundamentally public or private? Are there many different forms of play, or do all forms of play share certain characteristics (how can a single concept have plural meanings)? How is Huizinga’s conception of play related to the claim that the most basic form of play is animal play? How do we know that animals play?

Contrary to what the cover of the edition used here as illustration suggests, Johan Huizinga argues that not games, but archaic contest and ritual are the primary forms of play. Huizinga was the first to give a “definition” of play, while also insisting that play as such as indefinable, raising innumerable questions about play that have shaped philosophical inquiry ever since. What does he mean for instance when he writes that “play is freedom”? What idea of freedom is “at play” here? What are the different moral theories for which play might be relevant (utilitarian, deontological, and virtue-based)? Is play fundamentally public or private? Are there many different forms of play, or do all forms of play share certain characteristics (how can a single concept have plural meanings)? How is Huizinga’s conception of play related to the claim that the most basic form of play is animal play? How do we know that animals play?

Art as Play

Can art ever be playful? One way to explore this question is by looking a painting about play. How does the composition and use of perspective of Pieter Breughel the Elder’s Children’s Games relate to the isolated scenes of playing, and the style and way they are portrayed? How are we meant to “read” or interpret these miniature portrayals in turn? (How does our visual apprehension of them relate or inform our understanding and interpreting their meaning?) Is there an overall “vision” uniting the episodes (and what is the meaning of the spatially distinct scenes)? How does the take of this picture on children’s play in general raise questions about the play of children, and its relevance for understanding the play concept? Does the picture teach a “moral”, and if so in what sense? Does this picture play? More generally, what is the moral teaching of pictures, and is an idea of play indispensable to understanding how they relate to us and we to them?

While all painting is certainly embodied thinking, Breughel’s work seems to be particularly focused on reflecting on what painting is as a kind of material play. For more on the issue of embodiment, see LINK.

Can art ever be playful? One way to explore this question is by looking a painting about play. How does the composition and use of perspective of Pieter Breughel the Elder’s Children’s Games relate to the isolated scenes of playing, and the style and way they are portrayed? How are we meant to “read” or interpret these miniature portrayals in turn? (How does our visual apprehension of them relate or inform our understanding and interpreting their meaning?) Is there an overall “vision” uniting the episodes (and what is the meaning of the spatially distinct scenes)? How does the take of this picture on children’s play in general raise questions about the play of children, and its relevance for understanding the play concept? Does the picture teach a “moral”, and if so in what sense? Does this picture play? More generally, what is the moral teaching of pictures, and is an idea of play indispensable to understanding how they relate to us and we to them?

While all painting is certainly embodied thinking, Breughel’s work seems to be particularly focused on reflecting on what painting is as a kind of material play. For more on the issue of embodiment, see LINK.

Can art ever be playful? One way to explore this question is by looking a painting about play. How does the composition and use of perspective of Pieter Breughel the Elder’s Children’s Games relate to the isolated scenes of playing, and the style and way they are portrayed? How are we meant to “read” or interpret these miniature portrayals in turn? (How does our visual apprehension of them relate or inform our understanding and interpreting their meaning?) Is there an overall “vision” uniting the episodes (and what is the meaning of the spatially distinct scenes)? How does the take of this picture on children’s play in general raise questions about the play of children, and its relevance for understanding the play concept? Does the picture teach a “moral”, and if so in what sense? Does this picture play? More generally, what is the moral teaching of pictures, and is an idea of play indispensable to understanding how they relate to us and we to them?

While all painting is certainly embodied thinking, Breughel’s work seems to be particularly focused on reflecting on what painting is as a kind of material play. For more on the issue of embodiment, see LINK.

Virtuality

How did the emergence of virtual and digital spaces change the way we play? Are digital virtual spaces merely the true culmination of an aspiration of Western art since the Renaissance to “recreate the world in its own image” (as Andrè Bazin once wrote about photography), or do they represent a qualitatively different development? Are video games form of playing at all in a traditional sense? Apart from talking about and sharing our experiences with gaming, the best way to explore this question is by reading some classical accounts of first encounters with digital play, as well as studying the relationship between digital-based cinema and traditional film. Of particular interest is the question whether video games offer an enhanced or rather a reduced experience of ourselves as embodied creatures? Do time and space have different meanings in virtual reality? Has the emergence of digital virtual space put an end to our capacity for living in “reality” or in nature altogether, or has it precisely created new inspirations for returning to nature and for engaging and appreciating the materiality of the world in new ways?

How did the emergence of virtual and digital spaces change the way we play? Are digital virtual spaces merely the true culmination of an aspiration of Western art since the Renaissance to “recreate the world in its own image” (as Andrè Bazin once wrote about photography), or do they represent a qualitatively different development? Are video games form of playing at all in a traditional sense? Apart from talking about and sharing our experiences with gaming, the best way to explore this question is by reading some classical accounts of first encounters with digital play, as well as studying the relationship between digital-based cinema and traditional film. Of particular interest is the question whether video games offer an enhanced or rather a reduced experience of ourselves as embodied creatures? Do time and space have different meanings in virtual reality? Has the emergence of digital virtual space put an end to our capacity for living in “reality” or in nature altogether, or has it precisely created new inspirations for returning to nature and for engaging and appreciating the materiality of the world in new ways?

How did the emergence of virtual and digital spaces change the way we play? Are digital virtual spaces merely the true culmination of an aspiration of Western art since the Renaissance to “recreate the world in its own image” (as Andrè Bazin once wrote about photography), or do they represent a qualitatively different development? Are video games form of playing at all in a traditional sense? Apart from talking about and sharing our experiences with gaming, the best way to explore this question is by reading some classical accounts of first encounters with digital play, as well as studying the relationship between digital-based cinema and traditional film. Of particular interest is the question whether video games offer an enhanced or rather a reduced experience of ourselves as embodied creatures? Do time and space have different meanings in virtual reality? Has the emergence of digital virtual space put an end to our capacity for living in “reality” or in nature altogether, or has it precisely created new inspirations for returning to nature and for engaging and appreciating the materiality of the world in new ways?

Dark Play

Hemingway’s erudite account of the Spanish tradition of bullfighting as tragedy and as an existential dance with death is more than just a document of personal obsession. It is at once an account of the writer’s vocation under modern conditions, as well as an ironic critique of the perceived hypocrisy of modern culture which rejects such allegedly archaic, primitive, and cruel forms of entertainment while unleashing death and devastation on an unheard-of scale in mechanized war. While long out of print on account of its representation of heroism as maleness and its uncritical accepting of animal suffering, there is no better text to raise the milliard questions about the limits of play and “dark” play. Are there limits to the formal definition of play? Does genuine play always require empathy, or does it rather foster rationality in the face of empathy? Can the desire to win ever be justified apart from accepting the inevitability of hurting another person, even if in a fictional context? Are modern forms of playing with fate, such as gambling our only genuine means of reaffirming our finitude, or is it rather an outlet for culturally unacceptable desires? Is religion itself under modern conditions a form of dark play?

Hemingway’s erudite account of the Spanish tradition of bullfighting as tragedy and as an existential dance with death is more than just a document of personal obsession. It is at once an account of the writer’s vocation under modern conditions, as well as an ironic critique of the perceived hypocrisy of modern culture which rejects such allegedly archaic, primitive, and cruel forms of entertainment while unleashing death and devastation on an unheard-of scale in mechanized war. While long out of print on account of its representation of heroism as maleness and its uncritical accepting of animal suffering, there is no better text to raise the milliard questions about the limits of play and “dark” play. Are there limits to the formal definition of play? Does genuine play always require empathy, or does it rather foster rationality in the face of empathy? Can the desire to win ever be justified apart from accepting the inevitability of hurting another person, even if in a fictional context? Are modern forms of playing with fate, such as gambling our only genuine means of reaffirming our finitude, or is it rather an outlet for culturally unacceptable desires? Is religion itself under modern conditions a form of dark play?

Hemingway’s erudite account of the Spanish tradition of bullfighting as tragedy and as an existential dance with death is more than just a document of personal obsession. It is at once an account of the writer’s vocation under modern conditions, as well as an ironic critique of the perceived hypocrisy of modern culture which rejects such allegedly archaic, primitive, and cruel forms of entertainment while unleashing death and devastation on an unheard-of scale in mechanized war. While long out of print on account of its representation of heroism as maleness and its uncritical accepting of animal suffering, there is no better text to raise the milliard questions about the limits of play and “dark” play. Are there limits to the formal definition of play? Does genuine play always require empathy, or does it rather foster rationality in the face of empathy? Can the desire to win ever be justified apart from accepting the inevitability of hurting another person, even if in a fictional context? Are modern forms of playing with fate, such as gambling our only genuine means of reaffirming our finitude, or is it rather an outlet for culturally unacceptable desires? Is religion itself under modern conditions a form of dark play?

Humanistic Play

Friedrich Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man contain the possibly most often quoted sentence or “thesis” about play in the Western intellectual tradition: ‘Man only plays when he is in the fullest sense of the word a human being, and he is only fully a human being when he plays‘. Yet, weirdly, Schiller makes no effort to define play itself, and his representative examples of play involve engagement with the least playful works of art in existence, namely classical sculpture. The puzzle of trying to figure out what Schiller means by play is a worthwhile exercise in itself, but his work is also important as the source of the most dominant Western political tradition in thinking about play, namely liberal humanism. Can we really reconcile the many ambiguities and contradictions of human nature in a vision of a political future based on a form of enlightened humanism motivated by rational play as an ideal? Or is Schiller’s political project so deeply entangled with rhetoric justifying the human “right” to dominate nature that it is time to say goodbye to it? How can we re-imagine politics as play?

Friedrich Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man contain the possibly most often quoted sentence or “thesis” about play in the Western intellectual tradition: ‘Man only plays when he is in the fullest sense of the word a human being, and he is only fully a human being when he plays‘. Yet, weirdly, Schiller makes no effort to define play itself, and his representative examples of play involve engagement with the least playful works of art in existence, namely classical sculpture. The puzzle of trying to figure out what Schiller means by play is a worthwhile exercise in itself, but his work is also important as the source of the most dominant Western political tradition in thinking about play, namely liberal humanism. Can we really reconcile the many ambiguities and contradictions of human nature in a vision of a political future based on a form of enlightened humanism motivated by rational play as an ideal? Or is Schiller’s political project so deeply entangled with rhetoric justifying the human “right” to dominate nature that it is time to say goodbye to it? How can we re-imagine politics as play?

Friedrich Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man contain the possibly most often quoted sentence or “thesis” about play in the Western intellectual tradition: ‘Man only plays when he is in the fullest sense of the word a human being, and he is only fully a human being when he plays‘. Yet, weirdly, Schiller makes no effort to define play itself, and his representative examples of play involve engagement with the least playful works of art in existence, namely classical sculpture. The puzzle of trying to figure out what Schiller means by play is a worthwhile exercise in itself, but his work is also important as the source of the most dominant Western political tradition in thinking about play, namely liberal humanism. Can we really reconcile the many ambiguities and contradictions of human nature in a vision of a political future based on a form of enlightened humanism motivated by rational play as an ideal? Or is Schiller’s political project so deeply entangled with rhetoric justifying the human “right” to dominate nature that it is time to say goodbye to it? How can we re-imagine politics as play?

Games

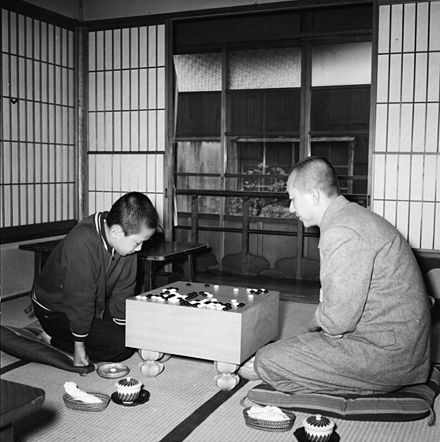

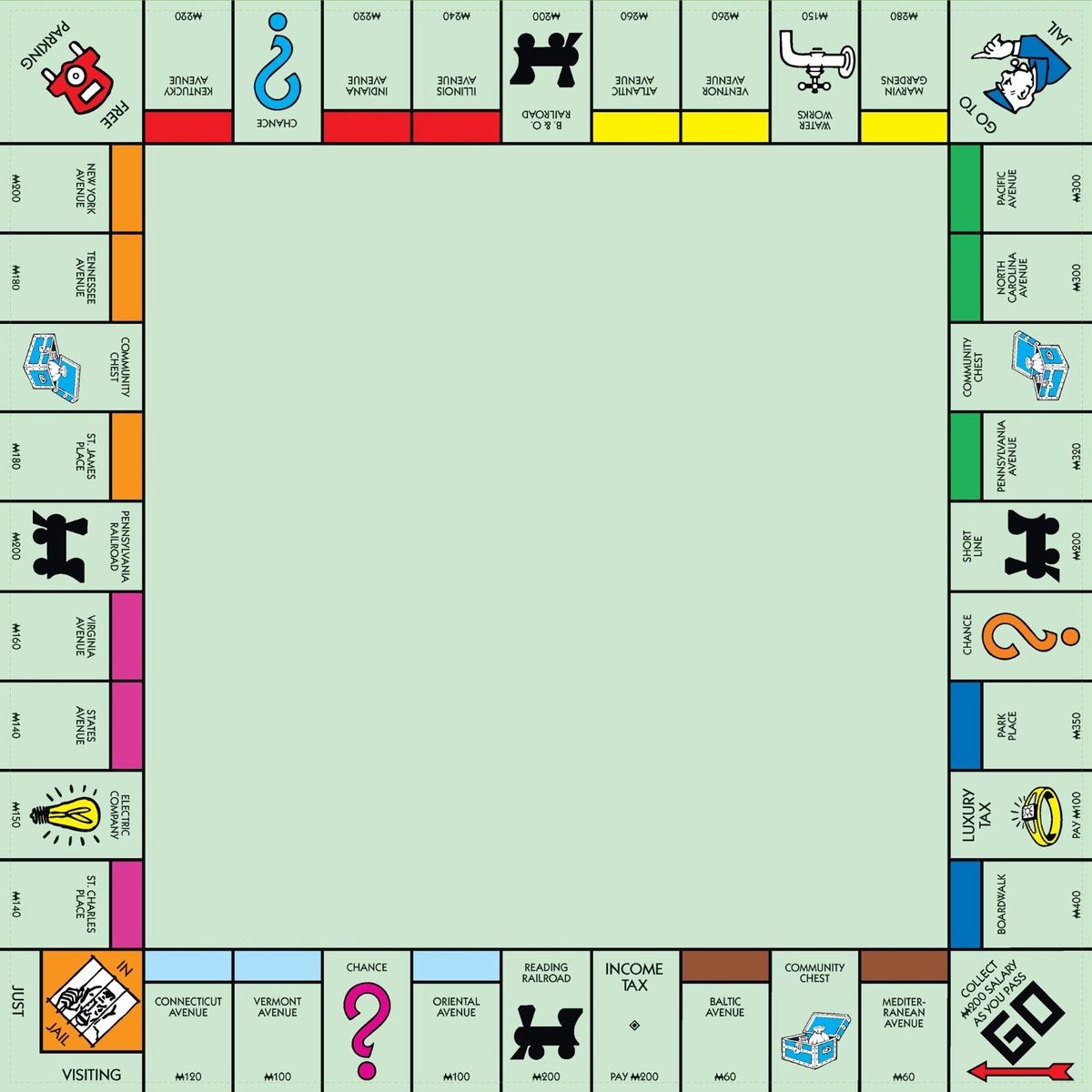

How should games figure into our efforts to take play seriously as fundamental to human life (or perhaps life in general) as well as social formations? On some accounts (such as Huzinga’s) games are merely distorted and decadent echoes of more original and genuine forms of play, such as a contest and ritual. Other accounts (such a Caillois) take games to be the most fundamental and representative forms of human play. Perhaps we can make some progress with this dilemma by asking ourselves some questions about games directly. What is a good game (for instance, does it always a require a mixture of strategy and chance)? What is a deep game (for instance, in the case of GO, chess or bridge, is it simply the strategic complexity that makes these games deep, or is it something else, such as the way they are expressive of a tradition)? Is gaming always a form of obsession, suggesting that there is always something unhealthy and geeky about committed players of certain games? How does the term “game” function as a metaphor in other contexts? Are there playful and non-playful way of playing games, and what does this distinction suggest about play as an activity vs attitude?

How should games figure into our efforts to take play seriously as fundamental to human life (or perhaps life in general) as well as social formations? On some accounts (such as Huzinga’s) games are merely distorted and decadent echoes of more original and genuine forms of play, such as a contest and ritual. Other accounts (such a Caillois) take games to be the most fundamental and representative forms of human play. Perhaps we can make some progress with this dilemma by asking ourselves some questions about games directly. What is a good game (for instance, does it always a require a mixture of strategy and chance)? What is a deep game (for instance, in the case of GO, chess or bridge, is it simply the strategic complexity that makes these games deep, or is it something else, such as the way they are expressive of a tradition)? Is gaming always a form of obsession, suggesting that there is always something unhealthy and geeky about committed players of certain games? How does the term “game” function as a metaphor in other contexts? Are there playful and non-playful way of playing games, and what does this distinction suggest about play as an activity vs attitude?

How should games figure into our efforts to take play seriously as fundamental to human life (or perhaps life in general) as well as social formations? On some accounts (such as Huzinga’s) games are merely distorted and decadent echoes of more original and genuine forms of play, such as a contest and ritual. Other accounts (such a Caillois) take games to be the most fundamental and representative forms of human play. Perhaps we can make some progress with this dilemma by asking ourselves some questions about games directly. What is a good game (for instance, does it always a require a mixture of strategy and chance)? What is a deep game (for instance, in the case of GO, chess or bridge, is it simply the strategic complexity that makes these games deep, or is it something else, such as the way they are expressive of a tradition)? Is gaming always a form of obsession, suggesting that there is always something unhealthy and geeky about committed players of certain games? How does the term “game” function as a metaphor in other contexts? Are there playful and non-playful way of playing games, and what does this distinction suggest about play as an activity vs attitude?

Winning and Victory

According to one much discussed definition, play is “the voluntary overcoming of unnecessary obstacles”. This suggests that competitiveness is essential to play, raising a whole host of further questions.In the case of games, one might go back to asking whether the only reason for playing games is to create artificial conditions for engaging in competition… Or is it the case rather that genuine play (the kind for which we think play is important) only arises when competition is engaged in playfully, i.e., in some non-serious or ameliorative way? Can one really make a distinction between “striving” play and competitive play, and if so, what does this tell us about the value of play? Is play valuable on account of the virtues it calls on us to exercise? Is wanting to win at games irrational, or is rather not wanting to (or not willing to want to) that is irrational?

According to one much discussed definition, play is “the voluntary overcoming of unnecessary obstacles”. This suggests that competitiveness is essential to play, raising a whole host of further questions.In the case of games, one might go back to asking whether the only reason for playing games is to create artificial conditions for engaging in competition… Or is it the case rather that genuine play (the kind for which we think play is important) only arises when competition is engaged in playfully, i.e., in some non-serious or ameliorative way? Can one really make a distinction between “striving” play and competitive play, and if so, what does this tell us about the value of play? Is play valuable on account of the virtues it calls on us to exercise? Is wanting to win at games irrational, or is rather not wanting to (or not willing to want to) that is irrational?

According to one much discussed definition, play is “the voluntary overcoming of unnecessary obstacles”. This suggests that competitiveness is essential to play, raising a whole host of further questions.In the case of games, one might go back to asking whether the only reason for playing games is to create artificial conditions for engaging in competition… Or is it the case rather that genuine play (the kind for which we think play is important) only arises when competition is engaged in playfully, i.e., in some non-serious or ameliorative way? Can one really make a distinction between “striving” play and competitive play, and if so, what does this tell us about the value of play? Is play valuable on account of the virtues it calls on us to exercise? Is wanting to win at games irrational, or is rather not wanting to (or not willing to want to) that is irrational?

Mathematics as play

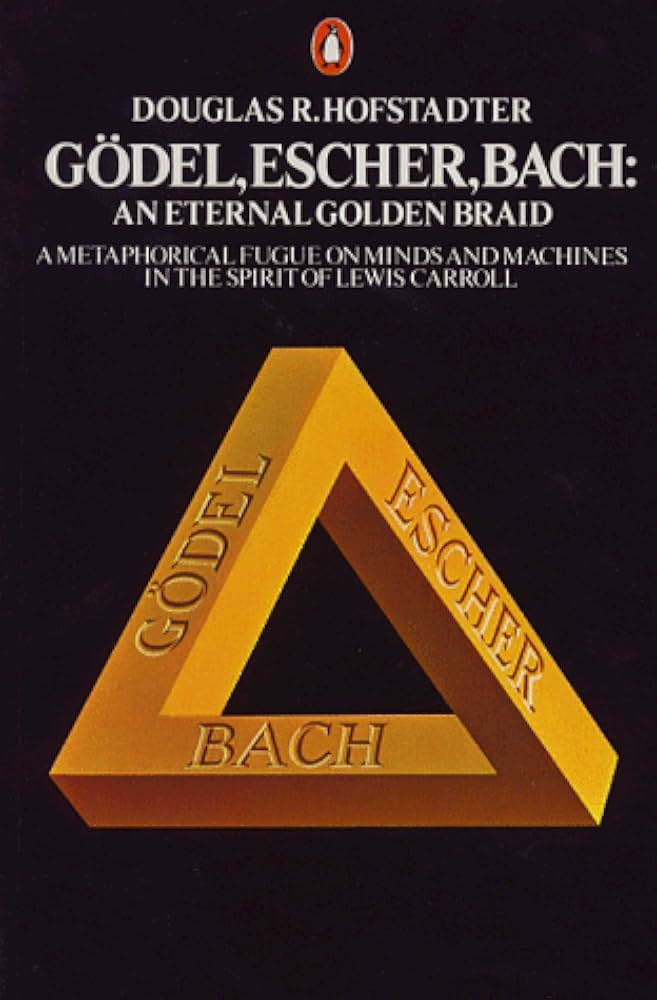

Some consideration of mathematical matters seems indispensable for a thorough consideration of play as a fundamental cultural phenomenon. For instance, game theoretical models of rationality suggest that games are fundamental to understanding the inherent constraints of decision making. One of the virtues of a broad-based consideration of the play phenomenon may be that such a question can even be raised and considered in a meaningful way. On the other hand, the modern conception of mathematics as a play with (or within) symbolic systems suggests the capacity for engaging with paradox (in turn, understood as a capacity for play) is the basis for appreciating the sui generis nature of human consciousness, transcending any dream of reproducing it by AI. Finally, is the question whether music is a form of mathematical play somehow related to these issues?

Some consideration of mathematical matters seems indispensable for a thorough consideration of play as a fundamental cultural phenomenon. For instance, game theoretical models of rationality suggest that games are fundamental to understanding the inherent constraints of decision making. One of the virtues of a broad-based consideration of the play phenomenon may be that such a question can even be raised and considered in a meaningful way. On the other hand, the modern conception of mathematics as a play with (or within) symbolic systems suggests the capacity for engaging with paradox (in turn, understood as a capacity for play) is the basis for appreciating the sui generis nature of human consciousness, transcending any dream of reproducing it by AI. Finally, is the question whether music is a form of mathematical play somehow related to these issues?

Some consideration of mathematical matters seems indispensable for a thorough consideration of play as a fundamental cultural phenomenon. For instance, game theoretical models of rationality suggest that games are fundamental to understanding the inherent constraints of decision making. One of the virtues of a broad-based consideration of the play phenomenon may be that such a question can even be raised and considered in a meaningful way. On the other hand, the modern conception of mathematics as a play with (or within) symbolic systems suggests the capacity for engaging with paradox (in turn, understood as a capacity for play) is the basis for appreciating the sui generis nature of human consciousness, transcending any dream of reproducing it by AI. Finally, is the question whether music is a form of mathematical play somehow related to these issues?

The Play of Children

Adventure playgrounds are inspired by the wish to acknowledge the autonomy in the play of children by securing absolute freedom for invention. Yet, as many discussions of this topic show, in our eagerness we often end up justifying the creation of such spaces despite the dangers by insisting that play has value for the developmental function it performs (this latter view is sometimes called the progressivist idea of play), hence denying that it has value in and for itself. But what if the value of the playful instinct or even the workings of human imagination is entirely independent of the developmental value it undoubtedly may have? What if the child’s imagination transcends the rational, perhaps even linking it to religious sentiment, calling for a theology rather than a theory of play? Or does the value of the play of children consist rather in total absorption, representing a state of “innocence” that our modern forms of playing can only ever aspire to? When we play, are we conscious (must we be conscious of playing (that we play), or does real playing require us to be at least forgetful of it?

Adventure playgrounds are inspired by the wish to acknowledge the autonomy in the play of children by securing absolute freedom for invention. Yet, as many discussions of this topic show, in our eagerness we often end up justifying the creation of such spaces despite the dangers by insisting that play has value for the developmental function it performs (this latter view is sometimes called the progressivist idea of play), hence denying that it has value in and for itself. But what if the value of the playful instinct or even the workings of human imagination is entirely independent of the developmental value it undoubtedly may have? What if the child’s imagination transcends the rational, perhaps even linking it to religious sentiment, calling for a theology rather than a theory of play? Or does the value of the play of children consist rather in total absorption, representing a state of “innocence” that our modern forms of playing can only ever aspire to? When we play, are we conscious (must we be conscious of playing (that we play), or does real playing require us to be at least forgetful of it?

Adventure playgrounds are inspired by the wish to acknowledge the autonomy in the play of children by securing absolute freedom for invention. Yet, as many discussions of this topic show, in our eagerness we often end up justifying the creation of such spaces despite the dangers by insisting that play has value for the developmental function it performs (this latter view is sometimes called the progressivist idea of play), hence denying that it has value in and for itself. But what if the value of the playful instinct or even the workings of human imagination is entirely independent of the developmental value it undoubtedly may have? What if the child’s imagination transcends the rational, perhaps even linking it to religious sentiment, calling for a theology rather than a theory of play? Or does the value of the play of children consist rather in total absorption, representing a state of “innocence” that our modern forms of playing can only ever aspire to? When we play, are we conscious (must we be conscious of playing (that we play), or does real playing require us to be at least forgetful of it?