“…if there is anything seriously to be called `the modern man,’ one fact about him is that what is natural to him is not natural, that naturalness for him has become a stupendous achievement.”

Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film ⟩⟩

Introduction

Modernism and its aftermath now span almost 200 years of history, yet few attempts have been made to reconsider how this prolific period in Western art and literature might engage with Friedrich Schiller’s ideas on aesthetic education, first published in 1795. One reason for this might be the vastness and diversity of the material—so expansive and complex that no account of modernism could ever claim to be complete. It could even be said that modernism is one of those themes whose very complexity makes amateurs of all of us. However, how could any serious approach to education, one that aims at self-knowledge, avoid confronting the question of what defines modern man? Perhaps it is the naïveté of this question that calls for an acceptance of the predicament of naïveté itself, a state we must approach with humility. But isn’t this naïveté precisely what modern art demands of itself? There is no alternative but to try, as best we can, to navigate the intricate web of relationships within modernism, searching for a path that provides at least a partial, satisfying picture of the whole.

Beauty

“The discovery that something can be good art without being beautiful [is] one of the great conceptual clarifications of twentieth-century philosophy of art, though it was made exclusively by artists.”

Arthur Danto, quoted in Only a Promise of Happiness: The Place of Beauty in a World of Art, by Alexander Nehamas

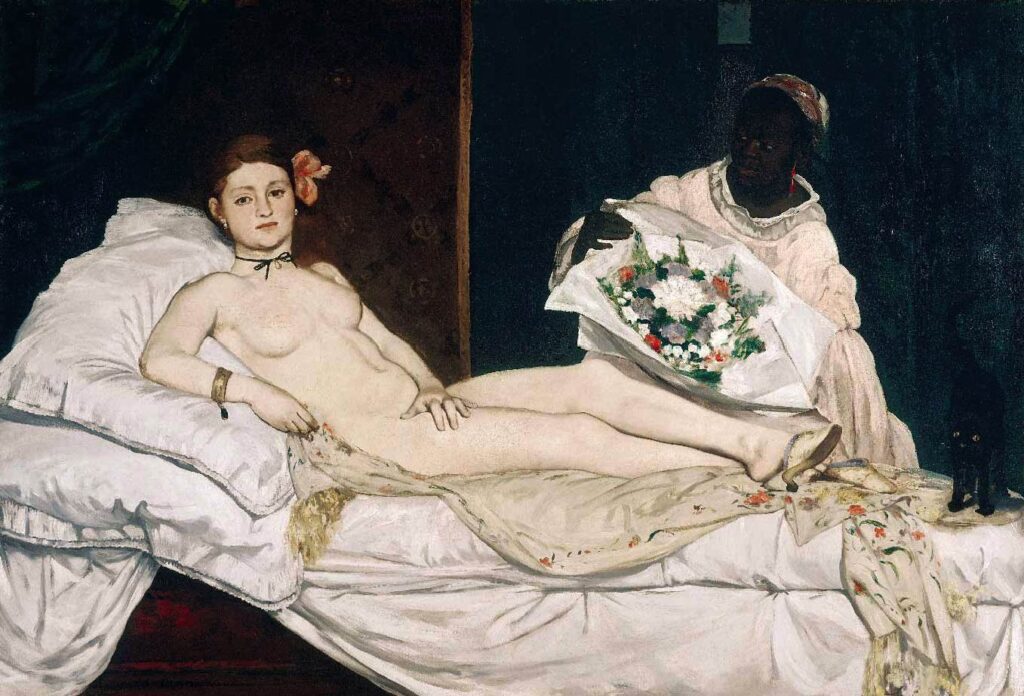

Beauty has always held a certain reassurance, whether understood as a material reflection of an intangible ideal, a harmonious balance of parts within a whole, or as the subject of the “judgment of taste.” Modernist works begin to question the legitimacy of striving for beauty in contexts and genres where this goal seems intrinsically linked to the very purpose of creating art (cf. Manet’s Olympia as a take on the traditional genre of the recumbent Venus). At the same time, numerous critics and theorists of modernist art (e.g., Benedetto Croce, Ortega y Gasset, Clive Bell, and Clement Greenberg) seem to argue that modernist art’s pursuit of “abstraction” ultimately distills to its essence what is truly aesthetic about artworks—namely, their formal qualities—and, thus, something akin to beauty in a traditional sense. While no definitive solution may resolve this paradoxical relationship between modernist art and beauty, exploring how this dialectic unfolds in the work of both philosophical critics and artists offers one of the clearest ways to engage with how modernist works reflect on their own identity and purpose, and hence on the meaning of modernism.

“The discovery that something can be good art without being beautiful [is] one of the great conceptual clarifications of twentieth-century philosophy of art, though it was made exclusively by artists.”

Arthur Danto, quoted in Only a Promise of Happiness: The Place of Beauty in a World of Art, by Alexander Nehamas

Beauty has always held a certain reassurance, whether understood as a material reflection of an intangible ideal, a harmonious balance of parts within a whole, or as the subject of the “judgment of taste.” Modernist works begin to question the legitimacy of striving for beauty in contexts and genres where this goal seems intrinsically linked to the very purpose of creating art (cf. Manet’s Olympia as a take on the traditional genre of the recumbent Venus). At the same time, numerous critics and theorists of modernist art (e.g., Benedetto Croce, Ortega y Gasset, Clive Bell, and Clement Greenberg) seem to argue that modernist art’s pursuit of “abstraction” ultimately distills to its essence what is truly aesthetic about artworks—namely, their formal qualities—and, thus, something akin to beauty in a traditional sense. While no definitive solution may resolve this paradoxical relationship between modernist art and beauty, exploring how this dialectic unfolds in the work of both philosophical critics and artists offers one of the clearest ways to engage with how modernist works reflect on their own identity and purpose, and hence on the meaning of modernism.

Architecture and Utopia

“The old structural forms which up to the present time have spelled `architecture’ are decayed. Their life went from them long ago and new conditions industrially, steel and concrete and terra cotta, are prophesying a more plastic art wherein as the flesh is to our bones so will the covering be to the structure, but more truly and beautifully expressive than ever.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, quoted in Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier: The Romantic Legacy, by Richard Etlin

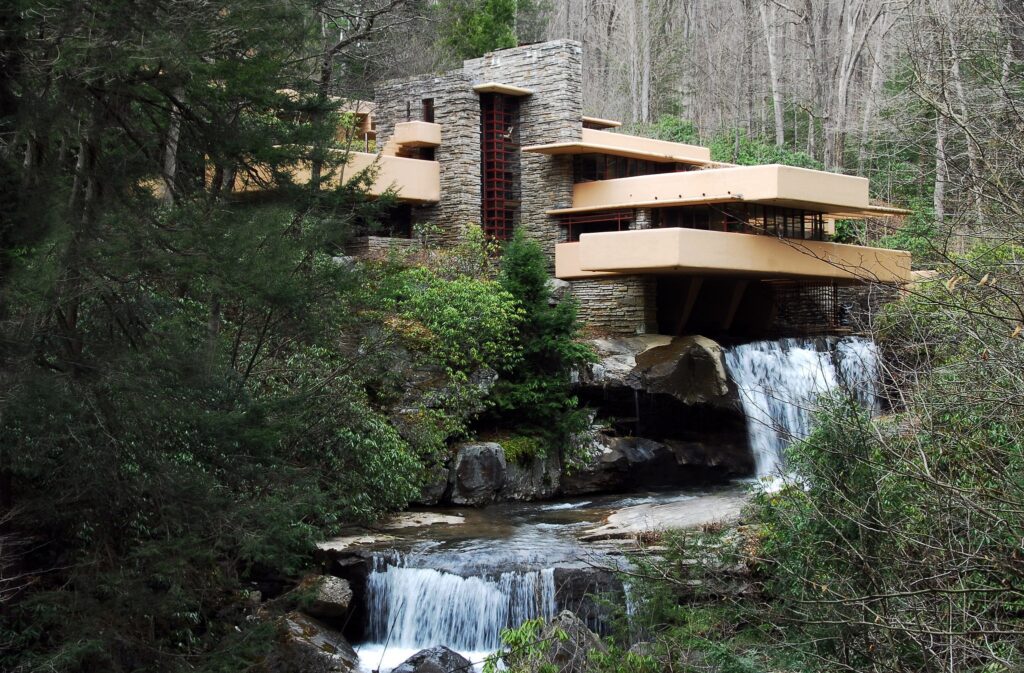

Modernism is frequently linked to a sense of crisis, yet modernist art—particularly before WWI—is just as often exhuberantly utopian. Georg Lukács, a prominent modernist critic turned Marxist thinker, noted in his later writings that the “specificity” of architecture as an art form lies in its inability to express anything “negative.” Whether one agrees with this view or not, it offers an explanation for why modernist architects and the creative communities they form—such as those around Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Bauhaus—are often the ones who embody utopian thinking. Confronted with the absence of a clear path toward fulfilling the traditional architectural aim of affirming social identity, modernist architects face the unique challenge of designing human-centered spaces that are both meaningful and implicitly political, all while rejecting prevailing social values and conditions. In practice, this thinking translates into the creation of restorative spaces that aim to heal the modern sense of dissonance between individuals’ private experiences and the outside world. As such, it is through the study of the works of modernist architects and their writings that we are most directly compelled to confront the misconception that modernism could be simply considered a revival of the Romantic ideal of “art for art’s sake.”

“The old structural forms which up to the present time have spelled `architecture’ are decayed. Their life went from them long ago and new conditions industrially, steel and concrete and terra cotta, are prophesying a more plastic art wherein as the flesh is to our bones so will the covering be to the structure, but more truly and beautifully expressive than ever.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, quoted in Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier: The Romantic Legacy, by Richard Etlin

Modernism is frequently linked to a sense of crisis, yet modernist art—particularly before WWI—is just as often exhuberantly utopian. Georg Lukács, a prominent modernist critic turned Marxist thinker, noted in his later writings that the “specificity” of architecture as an art form lies in its inability to express anything “negative.” Whether one agrees with this view or not, it offers an explanation for why modernist architects and the creative communities they form—such as those around Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Bauhaus—are often the ones who embody utopian thinking. Confronted with the absence of a clear path toward fulfilling the traditional architectural aim of affirming social identity, modernist architects face the unique challenge of designing human-centered spaces that are both meaningful and implicitly political, all while rejecting prevailing social values and conditions. In practice, this thinking translates into the creation of restorative spaces that aim to heal the modern sense of dissonance between individuals’ private experiences and the outside world. As such, it is through the study of the works of modernist architects and their writings that we are most directly compelled to confront the misconception that modernism could be simply considered a revival of the Romantic ideal of “art for art’s sake.”

Temporality

“What is time?”

ThomasMann: The Magic Mountain

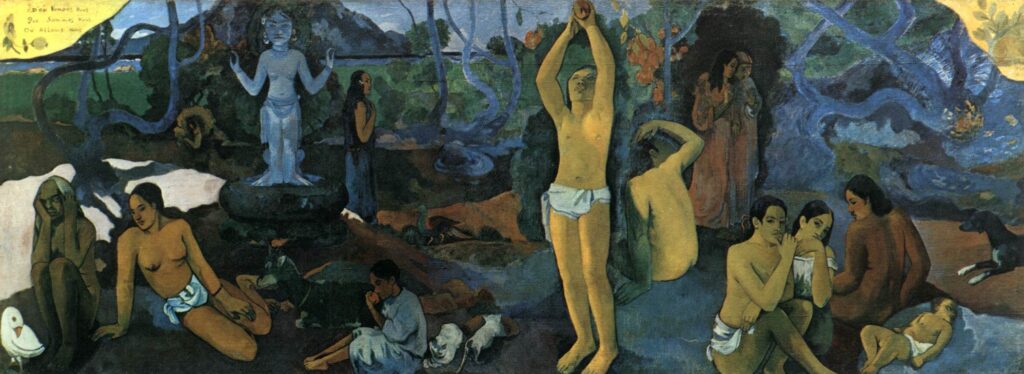

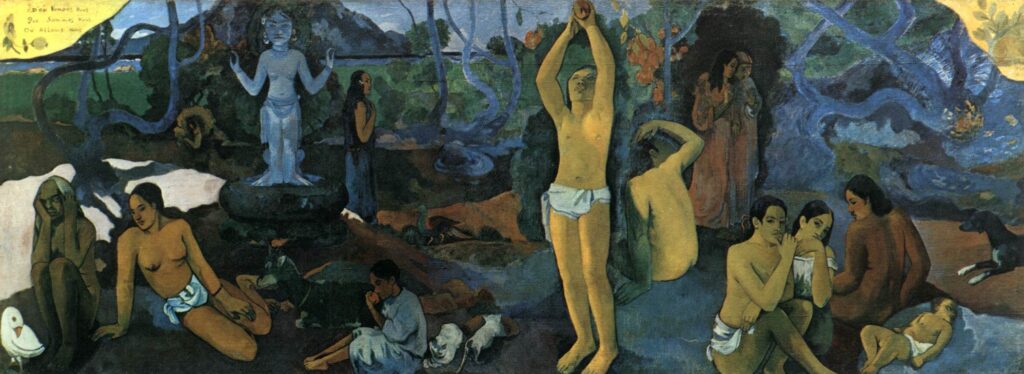

Nietzsche diagnoses the “decadence” afflicting modern man as a failure to live in the present, coupled with an inability to form a genuine, coherent sense of self by referencing the past. The kaleidoscopic evolution of modernist art can be seen as a series of direct responses to Nietzsche’s call for a new culture, one of “second immediacy” or “second innocence.” Each modernist movement seems to invent new ways of returning the viewer to the present by eliminating (narrative) time beginning with Impressionism’s focus on a-temporal “mood” conveyed through atmosphere, moving through Gauguin’s invocation of mythical timelessness, and culminating in Cubism’s rejection of temporality and the Surrealists’ embrace of dreams. In its effort to capture the timeless within the ordinary, modernism proposes a “history of the present.”

This sense of timelessness in modern art also aligns with the idea that the key to understanding the shift toward modernism lies not in a complete break with the past, but in the “banishing of all anecdotal elements” (Ernst Gombrich). But, given that human beings are still “beings in time,” have we lost art as a means of reflecting on who we are? Should we turn to the old masters for deeper truth and modern art for refreshment?

“What is time?”

ThomasMann: The Magic Mountain

Nietzsche diagnoses the “decadence” afflicting modern man as a failure to live in the present, coupled with an inability to form a genuine, coherent sense of self by referencing the past. The kaleidoscopic evolution of modernist art can be seen as a series of direct responses to Nietzsche’s call for a new culture, one of “second immediacy” or “second innocence.” Each modernist movement seems to invent new ways of returning the viewer to the present by eliminating (narrative) time beginning with Impressionism’s focus on a-temporal “mood” conveyed through atmosphere, moving through Gauguin’s invocation of mythical timelessness, and culminating in Cubism’s rejection of temporality and the Surrealists’ embrace of dreams. In its effort to capture the timeless within the ordinary, modernism proposes a “history of the present.”

This sense of timelessness in modern art also aligns with the idea that the key to understanding the shift toward modernism lies not in a complete break with the past, but in the “banishing of all anecdotal elements” (Ernst Gombrich). But, given that human beings are still “beings in time,” have we lost art as a means of reflecting on who we are? Should we turn to the old masters for deeper truth and modern art for refreshment?

Subjectivity

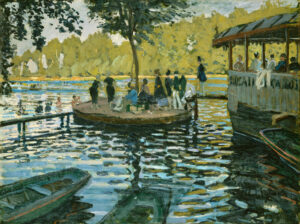

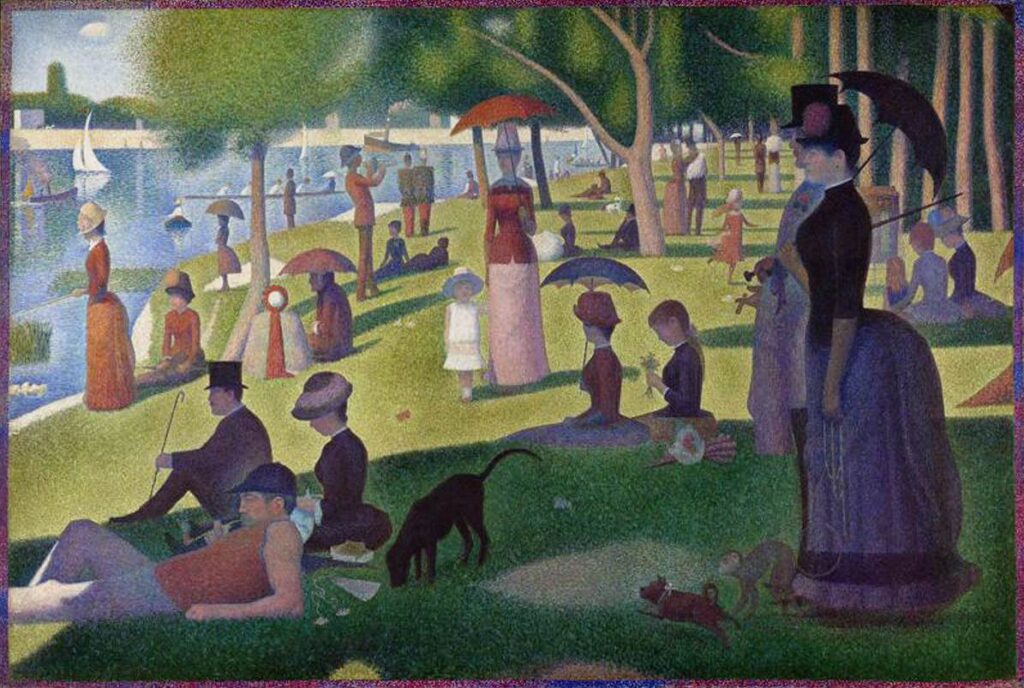

The so called problem of subjectivity proves to be surprisingly ambiguous upon closer examination. An impression, for instance, is something entirely “subjective”, formed within the consciousness of the perceiving subject, reflecting a personal point of view. Yet, it was Impressionist art that demanded the most accurate observation from the artist of how things actually appear in light, “en plein air,” leading to movements like Pointillism, which relied on “scientific” theories of color, and later Fauvism, where solidity is ensured by the exclusion of line.

Can we, then, say whether standing in front of a Cubist painting we are confronted with the artist’s subjective point of view, or a new technique better equipped to convey the spatial dimension of the world, making painting itself a “visible to the second power” (Merleau-Ponty)?

What, in the end, are the uses of the terms “objectivity” and “subjectivity” when talking about art?

The so called problem of subjectivity proves to be surprisingly ambiguous upon closer examination. An impression, for instance, is something entirely “subjective”, formed within the consciousness of the perceiving subject, reflecting a personal point of view. Yet, it was Impressionist art that demanded the most accurate observation from the artist of how things actually appear in light, “en plein air,” leading to movements like Pointillism, which relied on “scientific” theories of color, and later Fauvism, where solidity is ensured by the exclusion of line.

Can we, then, say whether standing in front of a Cubist painting we are confronted with the artist’s subjective point of view, or a new technique better equipped to convey the spatial dimension of the world, making painting itself a “visible to the second power” (Merleau-Ponty)?

What, in the end, are the uses of the terms “objectivity” and “subjectivity” when talking about art?

The so called problem of subjectivity proves to be surprisingly ambiguous upon closer examination. An impression, for instance, is something entirely “subjective”, formed within the consciousness of the perceiving subject, reflecting a personal point of view. Yet, it was Impressionist art that demanded the most accurate observation from the artist of how things actually appear in light, “en plein air,” leading to movements like Pointillism, which relied on “scientific” theories of color, and later Fauvism, where solidity is ensured by the exclusion of line.

Can we, then, say whether standing in front of a Cubist painting we are confronted with the artist’s subjective point of view, or a new technique better equipped to convey the spatial dimension of the world, making painting itself a “visible to the second power” (Merleau-Ponty)?

What, in the end, are the uses of the terms “objectivity” and “subjectivity” when talking about art?

Invention vs Discovery

Most accounts of modernism tend to emphasize a causal or expressive relationship between social change (or changes in human experience, subjectivity, or perception) and the dramatic transformations in the appearance of artworks. However, the bewildering array of new styles, along with the increasing expansion of what we accept as art, also gives rise to a series of new theories about what art is and how modern art relates to tradition.

Among the most intriguing of these approaches are those that arise from purely cognitivist theories of perception, which seek to explain modernism by examining the nature of representation and depiction. These theories often invite us to consider our experience of modernist technique directly.For example, some accounts suggest that the key to understanding an impressionist painting lies in our psychological ability to perceive a brushstroke as both a brushstroke and as, say, the reflection of light on water within the same act of perception. But do we truly have this capacity? And if we do, does this suggest that such perceptual abilities are intrinsic to human perception itself, thus making modernism more continuous with tradition than we may be inclined to believe? Are the ways in which traditional painting draws attention to the twofoldness of depiction and material medium different from the modernist practice of the same technique?

Finally, does it matter for our appreciation of modernist art whether we view these elements of technique as inventions or discoveries?

Most accounts of modernism tend to emphasize a causal or expressive relationship between social change (or changes in human experience, subjectivity, or perception) and the dramatic transformations in the appearance of artworks. However, the bewildering array of new styles, along with the increasing expansion of what we accept as art, also gives rise to a series of new theories about what art is and how modern art relates to tradition.

Among the most intriguing of these approaches are those that arise from purely cognitivist theories of perception, which seek to explain modernism by examining the nature of representation and depiction. These theories often invite us to consider our experience of modernist technique directly. For example, some accounts suggest that the key to understanding an impressionist painting lies in our psychological ability to perceive a brushstroke as both a brushstroke and as, say, the reflection of light on water within the same act of perception. But do we truly have this capacity? And if we do, does this suggest that such perceptual abilities are intrinsic to human perception itself, thus making modernism more continuous with tradition than we may be inclined to believe? Are the ways in which traditional painting draws attention to the twofoldness of depiction and material medium different from the modernist practice of the same technique?

Finally, does it matter for our appreciation of modernist art whether we view these elements of technique as inventions or discoveries?

The Ecstasy of Touch

“…painting looks toward this secret and feverish genesis of things in our body…”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

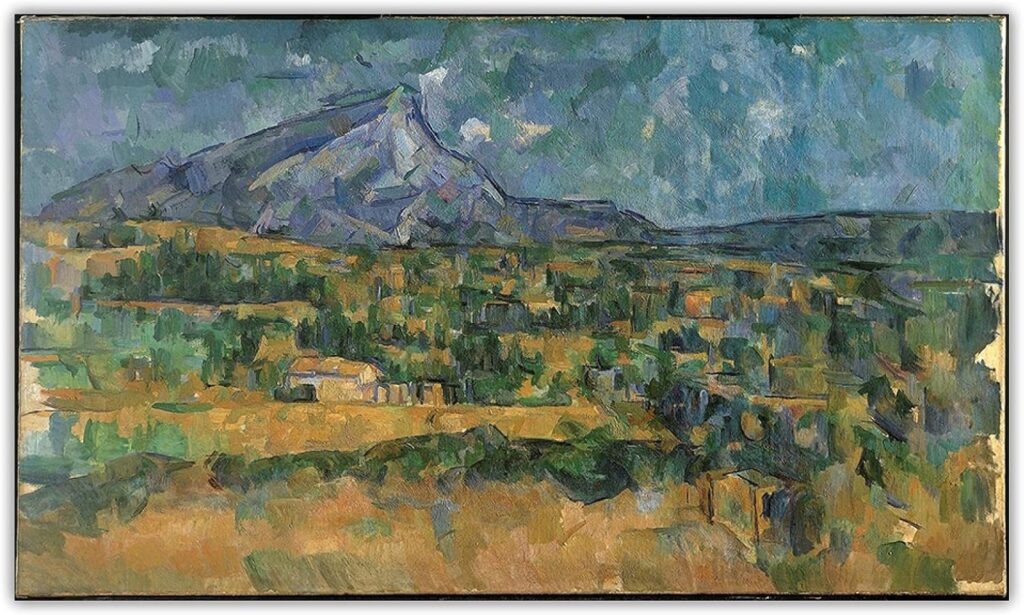

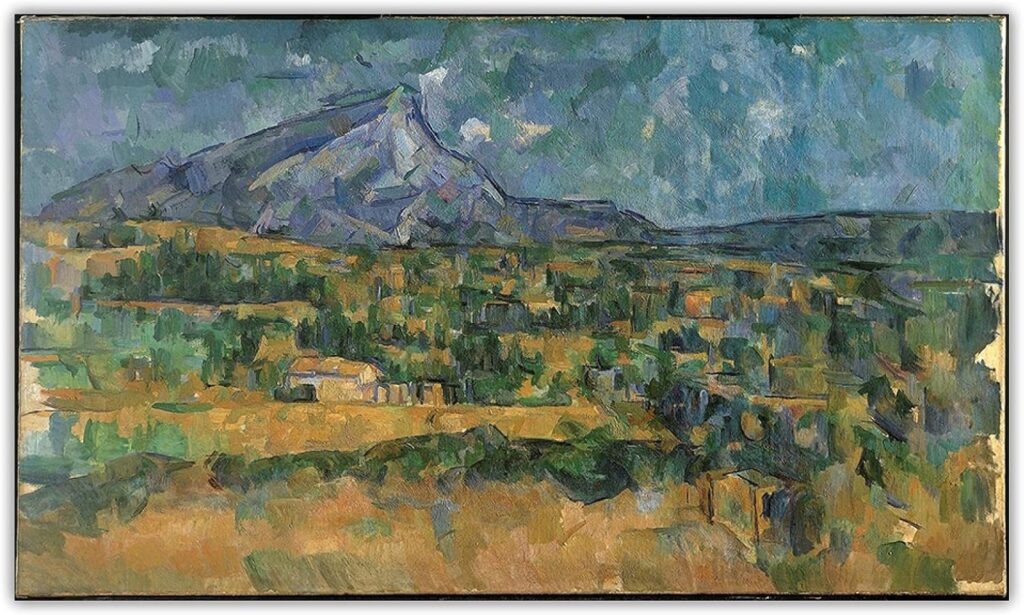

Which is the more fundamental human capacity for perceiving and navigating the external world: vision or touch? Modernist art turns this question into an exploration of the meaning and origin of abstraction. On one hand, abstraction can be seen as eliminating geometric perspective and the ability to render three-dimensional space, a hallmark of painting since the Renaissance. If vision is central to our relationship with reality, this may feel like the tragic culmination of a process by which the fact of human embodiment gradually loses its significance for art. On the other hand, many theorists and artists, including Picasso and the Cubists, view abstraction as an effort to restore the three-dimensional solidity of objects, linking perception of space and solidity to movement and touch. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty suggests Cézanne’s paintings “awaken powers dormant in ordinary vision,” showing how things “become things, and the world becomes world.”1 Does abstraction distance us from or reconnect us with material reality? Does modernism reveal that painting has always affirmed embodiment? Perhaps the best answer lies in looking at and discussing the works themselves.

1 See, Merleau-Ponty, M. 1993. “Eye and Mind.” In The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting, G. Johnson, 121–49. Evanston, Illinois. p. 141-2.

“…painting looks toward this secret and feverish genesis of things in our body…”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Which is the more fundamental human capacity for perceiving and navigating the external world: vision or touch? Modernist art turns this question into an exploration of the meaning and origin of abstraction. On one hand, abstraction can be seen as eliminating geometric perspective and the ability to render three-dimensional space, a hallmark of painting since the Renaissance. If vision is central to our relationship with reality, this may feel like the tragic culmination of a process by which the fact of human embodiment gradually loses its significance for art. On the other hand, many theorists and artists, including Picasso and the Cubists, view abstraction as an effort to restore the three-dimensional solidity of objects, linking perception of space and solidity to movement and touch. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty suggests Cézanne’s paintings “awaken powers dormant in ordinary vision,” showing how things “become things, and the world becomes world.”1 Does abstraction distance us from or reconnect us with material reality? Does modernism reveal that painting has always affirmed embodiment? Perhaps the best answer lies in looking at and discussing the works themselves.

1 See, Merleau-Ponty, M. 1993. “Eye and Mind.” In The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting, G. Johnson, 121–49. Evanston, Illinois. p. 141-2.

Innocence and Experience

Modernism as a movement can be understood as a sustained and diverse rebellion against societal conventions that are perceived to have lost their meaning, which, in turn, have the potential to distort private lives, turning them into a kind of lie (Ibsen). This explains the rise of the threat of kitsch, the various forms in which modernist art seeks purity, sincerity, and innocence, and the increasing speed with which each avant-garde movement is accused by the next of forgetting its origin in protest. But how exactly do we distinguish between “sincere” and “conformist” art? If this distinction is tied to the artist’s intention (or the intention behind the work), how do we identify and evaluate such intentions? Can modernist artworks truly educate us to recognize the difference between our false and true needs? Is innocence a condition of soul one can strive for at all?

Modernism as a movement can be understood as a sustained and diverse rebellion against societal conventions that are perceived to have lost their meaning, which, in turn, have the potential to distort private lives, turning them into a kind of lie (Ibsen). This explains the rise of the threat of kitsch, the various forms in which modernist art seeks purity, sincerity, and innocence, and the increasing speed with which each avant-garde movement is accused by the next of forgetting its origin in protest. But how exactly do we distinguish between “sincere” and “conformist” art? If this distinction is tied to the artist’s intention (or the intention behind the work), how do we identify and evaluate such intentions? Can modernist artworks truly educate us to recognize the difference between our false and true needs? Is innocence a condition of soul one can strive for at all?

Modernism as a movement can be understood as a sustained and diverse rebellion against societal conventions that are perceived to have lost their meaning, which, in turn, have the potential to distort private lives, turning them into a kind of lie (Ibsen). This explains the rise of the threat of kitsch, the various forms in which modernist art seeks purity, sincerity, and innocence, and the increasing speed with which each avant-garde movement is accused by the next of forgetting its origin in protest. But how exactly do we distinguish between “sincere” and “conformist” art? If this distinction is tied to the artist’s intention (or the intention behind the work), how do we identify and evaluate such intentions? Can modernist artworks truly educate us to recognize the difference between our false and true needs? Is innocence a condition of soul one can strive for at all?

The New Ontology

How are we affected by photography and film, and what do these mediums reflect about us as modern subjects that we are so deeply moved by them? For philosopher Stanley Cavell, the issue has two sides. On one hand, our attraction to film and photography reflects a modern sense of isolation; these mediums, with their inherent automatism, “make our sense of isolation appear natural to us.” On the other hand, because film is not just a modern art form, but also “the last traditional art under conditions of modernism,” it offers a unique opportunity to address this predicament. Film, as an art, has the potential to transform this sense of isolation into a search for a new innocence—how do we find trust in one another when we no longer feel we can truly know each other? For Cavell, the most productive way to engage with these questions is to immerse ourselves in the masterpieces of early European and Hollywood cinema. These films, which creatively and spontaneously employ the techniques of a new technology, make sense of the human condition in moments of historical upheaval, all the while relying on traditional narrative forms.

How are we affected by photography and film, and what do these mediums reflect about us as modern subjects that we are so deeply moved by them? For philosopher Stanley Cavell, the issue has two sides. On one hand, our attraction to film and photography reflects a modern sense of isolation; these mediums, with their inherent automatism, “make our sense of isolation appear natural to us.” On the other hand, because film is not just a modern art form, but also “the last traditional art under conditions of modernism,” it offers a unique opportunity to address this predicament. Film, as an art, has the potential to transform this sense of isolation into a search for a new innocence—how do we find trust in one another when we no longer feel we can truly know each other? For Cavell, the most productive way to engage with these questions is to immerse ourselves in the masterpieces of early European and Hollywood cinema. These films, which creatively and spontaneously employ the techniques of a new technology, make sense of the human condition in moments of historical upheaval, all the while relying on traditional narrative forms.

How are we affected by photography and film, and what do these mediums reflect about us as modern subjects that we are so deeply moved by them? For philosopher Stanley Cavell, the issue has two sides. On one hand, our attraction to film and photography reflects a modern sense of isolation; these mediums, with their inherent automatism, “make our sense of isolation appear natural to us.” On the other hand, because film is not just a modern art form, but also “the last traditional art under conditions of modernism,” it offers a unique opportunity to address this predicament. Film, as an art, has the potential to transform this sense of isolation into a search for a new innocence—how do we find trust in one another when we no longer feel we can truly know each other? For Cavell, the most productive way to engage with these questions is to immerse ourselves in the masterpieces of early European and Hollywood cinema. These films, which creatively and spontaneously employ the techniques of a new technology, make sense of the human condition in moments of historical upheaval, all the while relying on traditional narrative forms.